Letters and More

India at Age Twenty: Reflections

At the time it seemed like an interesting Friday night diversion. Being a political science major, I thought I might learn something useful. I never imagined I’d be among the chosen few for Project India. I never anticipated how it would influence my life.

As far back as I can remember it was my intention to become a journalist but covering sports for the LA Times not Asia and Africa, among other assignments, for CBS News and PBS. Never mind that my primary focus on international affairs shifted towards China and southern Africa, it was that summer in India that was the catalyst for things to come.

In Lucknow, spending hours with student leaders whose campus was closed following demonstrations against government policies, inspired an idealistic belief in the potential role of student government—at least until, as ASUCLA President, I encountered the machinations of UCLA Chancellor Raymond Allen and Dean Milton Hahn.

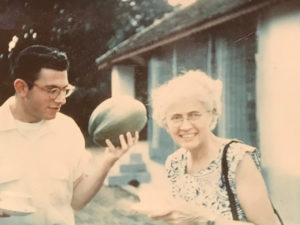

In Trivandrum, India, 1954.

In 1954, I was able to stand in India and point to Brown vs. The Board of Education as the start of a new day for racial equality in America. In 1965, on “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama, I stood at the Edmund Pettus Bridge with three camera crews and that night broadcast those indelible images to a nation still struggling to live up to its ideals and institutional guarantees.

When I got on the plane to India, I carried with me an inadequate knowledge of history and a political innocence that brings to mind the phrase “callow youth”. But it was also the start of a journey that led me to a post-graduate degree in East Asian Studies at Harvard, an academic path inspired at UCLA by professors Coleman and Kaplan, Steiner and Shields.

And, I had learned some valuable lessons during that summer of 1954. For one thing, India taught me that misperceptions and misinformation between nations and cultures was a two-way street (Indian students didn’t understand or know any more about us than we did about them). And that in exploring these issues, there was no substitute for personal experience, whether you were an Indian or an American.

There also is something about having to confront a skeptical and sometimes hostile audience determined to challenge America’s foreign policy, its social fabric and its popular culture (no matter how well-taken the criticisms might have been) in 90-degree heat and humidity that either utterly demoralizes a relatively inexperienced 20-year-old or builds resolve and self-confidence. Either it is intimidating, or you stand up in return, challenging the caste system, religious intolerance and uncritical admiration for the Soviet Union. And then, of course, you stage a musical review a cappella.

We were supposed to engage Indian students in manual labor. But hey, manual labor was not high on MY list of things to do, certainly not when it meant getting up at six a.m., bathing and shaving with cold water and riding the rear-end of a jeep to an outlying village. Nor did I know the first thing about building a one-room schoolhouse. But we pressed on.

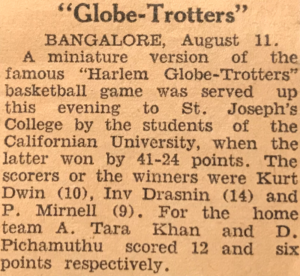

We were UCLA, even we were winning basketball games in those days.

It was another thing to arise before dawn to observe the rituals along the Ganges River during a trip to Benares, a side-trip intended to offer respite and relief from our daily grind and enhance our understanding of India. But where was the relief if a senior member of your group, an adult escort declares the Temple of Love—a culturally and religiously important local attraction of particular interest to serious students, depicting the one-hundred “basic positions” (one-hundred? basic?)—to be off limits? Miraculously, during the afternoon “rest period,” we found our way there and having partaken of this forbidden fruit, we pressed on.

We were told to be careful about what we ate and drank but without offending Indian sensibilities. No one explained how, exactly, to drop a purification pill into a glass of water or how to wash your hands before using them to eat off a banana leaf in the crowded company of local hosts and peers, without quite possibly offending them. Or, why you couldn’t eat that particular morsel of whatever it was but were afraid to ask. For religious reasons? Well surely, Indians would understand THAT.

Along the way, in Bombay and Delhi, we were counseled by US officials on American policy and Indian reality: some of it simplistic, the arrogance of power and piety; some of it thoughtful, informed and open-minded. We did not always, not easily, make immediate sense of it even though we probably thought we did.

After graduate school, I started out at United Press International and then moved on to broadcast news and public affairs where from time to time I did realize my boyhood ambition to cover major sporting events. But during several years as a producer-writer for the CBS Evening News I took greater pride in helping to cover events fundamental to the American idea and its promise, in particular the civil rights movement. And most rewarding of all has been the opportunity to focus my attention on Asia, especially in films that have tracked the story of China and US-China relations during the past forty years.

Was Project India a good idea? No doubt. Did we make a difference? In India, it is impossible to say but probably not much of one. In our own lives? No question. In looking through a bunch of old file folders I came across an article written about PI ’54 which included these statistics: it said ours was a five-thousand-mile trek around India, consisting of 16-hour days over the course of which we had an average weight loss of 12-pounds. In another file is the claim that in the Trivandrum area alone, we spoke or interacted with an estimated 6,529 Indian students. I have no idea where any of these numbers came from or how they were calculated but there they are. Perhaps the most remarkable number of all is that 50-plus years later we’re still talking about it, that it is still a part of our lives.

There are travel posters that refer to India as “The Land of Enlightenment”. There was no guarantee of enlightenment to be found in our experience. And despite the ideals and enthusiasms of youth, sooner or later you learn that your good intentions and hard work are not necessarily going to change the world. But you have to start somewhere and sometimes, change happens. Maybe changing a few minds, including our own, learning about ourselves as well as others in that long-ago summer, was an important place to begin.