Letters and More

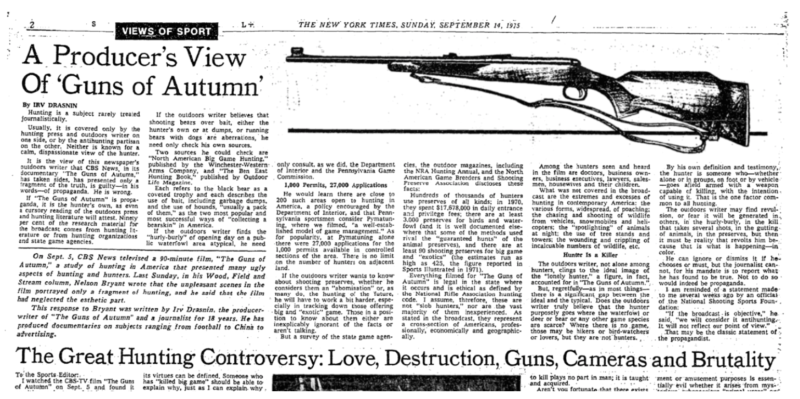

An estimated 37,000 letters and post cards later (at the time deemed a record number for a CBS News documentary), The New York Times afforded me space to respond to its outdoors writer, Nelson Bryant, who I’ve been told is a very good man even if he didn’t approve of The Guns of Autumn. My piece specifically addressed Mr. Bryant’s claims and complaints and was printed in the Sunday edition, September 14, 1975 under the headline: “A Producer’s View of ‘Guns of Autumn’”.

“Hunting is a subject rarely treated as journalism.

Usually, it is covered only by the hunting press and outdoors writer on one side, or by the antihunting partisan on the other. Neither is known for a calm, dispassionate view of the hunter.

It is the view of this newspaper’s outdoors writer that CBS News, in its documentary “The Guns of Autumn”, has taken sides, has presented only a fragment of the truth, is guilty — in his words — of propaganda. He is wrong.

If “The Guns of Autumn” is propaganda, it is the hunter’s own, as even a cursory reading of the outdoors press and hunting literature will attest. Ninety per cent of the research material for the broadcast comes from hunting literature or from hunting organizations and state game agencies.

If the outdoors writer believes that shooting bears over bait, either the hunter’s own or at dumps, or running bears with dogs are aberrations, he need only check his own sources.

Two sources he could check are “North American Big Game Hunting”, published by the Winchester-Western Arms Company, and “The Ben East Hunting Book”, published by Outdoor Life Magazine.

Each refers to the black bear as a coveted trophy and each describes the use of bait, including garbage dumps, and the use of hounds, “usually a pack of them”, as the two most popular and most successful ways of “collecting a bearskin” in America.

If the outdoors writer finds the “hurly-burly” of opening day on a public waterfowl area atypical, he need only consult, as we did, the Department of Interior and the Pennsylvania Game Commission.

He would learn there are close to 200 such areas open to hunting in America, a policy encouraged by the Department of Interior, and that Pennsylvania sportsmen consider Pymatuning, where we filmed, “a well-established model of game management.” As for popularity, at Pymatuning alone there were 27,000 applications for the 1,000 permits available in controlled sections of the area. There is no limit on the number of hunters on adjacent land.

If the outdoors writer wants to know about shooting preserves, whether he considers them an “abomination” or, as many do, the hunting of the future, he will have to work a bit harder, especially in tracking down those offering big and “exotic” game. Those in a position to know about them either are inexplicably ignorant of the facts or aren’t talking.

But a survey of the state game agencies, the outdoors magazines, including the NRA Hunting Annual, and the North American Game Breeders and Shooting Preserves Association discloses these facts:

Hundreds of thousands of hunters use preserves of all kinds; in 1970, they spent $17,678,000 in daily entrance and privilege fees; there are at least 3,000 preserves for birds and waterfowl (and it is well documented elsewhere that some of the methods used rival the “guaranteed hunts” of the animal preserves) and there are at least 90 shooting preserves for big game and “exotics” (the estimates run as high as 425, the figure reported in Sports Illustrated in 1971).

Everything filmed for “The Guns of Autumn” is legal in the state where it occurs and is ethical as defined by the National Rifle Association hunting code. I assume, therefore, these are not “slob hunters”, nor are the vast majority of them inexperienced. As stated in the broadcast, they represent a cross-section of Americans, professionally, economically and geographically.

Among the hunters seen and heard in the film are doctors, business owners, business executives, lawyers, salesmen, housewives and their children.

What was not covered in the broadcast are the extremes and excesses of hunting in contemporary America: the various forms, widespread, of poaching; the chasing and shooting of wildlife from vehicles, snowmobiles and helicopters; the ”spotlighting” of animals at night; the use of tree stands and towers; the wounding and crippling of incalculable numbers of wildlife, etc.

The outdoors writer, not alone among hunters, clings to the ideal image of the “lonely hunter,” a figure, in fact, accounted for in “The Guns of Autumn.”

But regretfully — as in most things — there is a significant gap between the ideal and the typical. Does the outdoors writer truly believe that the hunter purposely goes where the waterfowl or deer or bear or any other game species are scarce? Where there is no game, those may be hikers or bird-watchers or lovers, but they are not hunters.

By his own definition and testimony, the hunter is someone who — whether alone or in groups, on foot or by vehicle — goes afield armed with a weapon capable of killing, with the intention of using it. That is the one factor common to all hunting.

The outdoors writer may find revulsion, or fear it will be generated in others, in the hurly-burly, in the kill that takes several shots, in the gutting of animals, in the preserves, but then it must be reality that revolts him because that is what is happening — in color.

He can ignore or dismiss it if he chooses or must, but the journalist cannot, for his mandate is to report what he has found to be true. Not to do so would indeed be propaganda.

I am reminded of a statement made to me several weeks ago by an official of the National Shooting Sports Foundation:

“If the broadcast is objective,” he said, “we will consider it antihunting. It will not reflect our point of view.”

That may be the classic statement of the propagandist.”