Letters and More

Five Decades of U.S. Engagement with China: What Have We Learned?

Reflections on Covering China: A Journalist Looks Back

Wingspread Conference Center, November 3, 2018

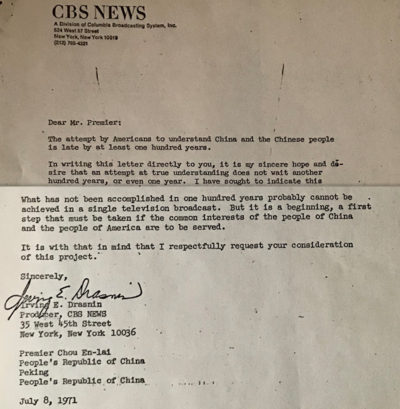

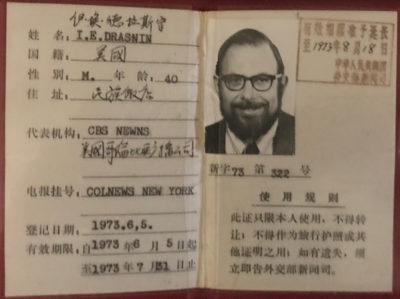

My four-page letter, to Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, July 1971. Did he ever see it? Did it help me get into China to film in 1973? I’ll never know.

To go back fifty years and reflect on the US-China relationship is not an easy assignment. If there’s one lesson I’ve learned, it’s this: Misunderstanding China is much easier than understanding China.

In 1966, or just more than fifty years ago, I was a producer on the CBS Evening News. One afternoon I was summoned to the videotape room and shown film of bobbing heads in the Yangtze River, and was asked: “Is that Mao?” Finally, I thought, a chance to use my background and training. Then, I thought, why would Mao be swimming in the Yangtze?

I took a long, hard look and spoke with authority: “Right there”, I said, “there is a resemblance, I think. It’s possible, I guess. Maybe, it’s hard to say. Where did this film come from, anyway?” In short, how did I know? Seeing China clearly has always been a challenge. But when the opportunity came, we did our best to set the record straight.

There were cautious beginnings during the 1970’s. We were well-intentioned, believing that ignorance, and animosity, and history could be overcome only by understanding it. We meant to inform and enlighten hoping that reason might prevail. I suppose that now, that sounds pitifully naïve. But then, after more than 20 years of mutual estrangement and two wars in Asia, it seemed the responsible thing to do.

In those days, we came to Wingspread, to consider American Press Coverage of China, a difficult undertaking at best, which I had experienced first-hand in 1973. To paraphrase the title of an Ingmar Bergman film, it had been like “Looking Through A Haze Darkly”. The haze was cigarette smoke, and a smokescreen of statistics.

In 1973, the Chinese idea of press coverage, everywhere you went, was a recitation of comparative statistics: pre-liberation and post-liberation, pre-liberation and post-liberation. Filming was a struggle, Chinese planning versus American spontaneity. Access versus denial.

In 1973, the Chinese idea of press coverage, everywhere you went, was a recitation of comparative statistics: pre-liberation and post-liberation, pre-liberation and post-liberation. Filming was a struggle, Chinese planning versus American spontaneity. Access versus denial.

At the #1 Diesel Engine Factory in Shanghai, when a worker dared to tell us about the violent confrontations there during the cultural revolution, I motioned to the camera crew to set up. But before I could ask the first question, the local revolutionary committee intervened. It would not be convenient, we were told, to film today. Please come back tomorrow.

When we returned, the dirt and grime of the factory grounds, including trucks and equipment, had been cleaned up. And the worker I wanted to interview? Sorry, he couldn’t be here today. Please, film whatever you like.

By the end of the 70’s, we were filming Deng Xiaoping in a stage coach, waving a ten-gallon hat, in a wild west show, in Houston. It was called normalization. The headline could well have been: “Capitalist Roaders, Unite!”

In 1982, making a documentary film in China was a different experience. There was room to maneuver, and for the process of discovery. You could walk into Peking University and Fudan University with a camera crew and interview students who spoke of Mao’s mistakes, and the cultural revolution, and hear answers like this:

“Many cadres died, many scientists died, and many people suffered in our university,” they told us. As well as: “Now, there is a problem of bribery, of bureaucracy, of some leaders taking money for themselves—that’s a big problem today.”

Outside the office of the Communist Youth League in Changsha, we asked two young men what they thought of Mao. Their answer: “Who”?

At the site of the 1978 Democracy Wall, we found an open-air roller-skating rink now used by unemployed and restless youth of a lost generation.

At the Beijing Broadcasting Institute, we interviewed and filmed students rehearsing for a city-wide talent competition, singing “We Shall Overcome” and reciting Martin Luther King’s speech “I Have a Dream”.

When asked what the new party line, the four modernizations, meant to them, one student said: “Freedom, we’re all equal under the law”.

About changes in China at that time, the novelist, Ding Ling, said to us: “They wouldn’t have been possible if Mao hadn’t died. It’s true”, she said, “I’m brave enough to say it’s true.”

At the editing table in New York City Looking for Mao for Frontline on PBS (1982-83). It took us about 60,000 feet of film to find him.

Would the authorities have approved the filming of these and other signs of change since Mao’s death? Not likely. But at the time there was an openness, a sense of possibility—not that the Chinese wanted to be like us, but that they didn’t want a return to Maoism and the cultural revolution, either. To some, it might have seemed a window through which to see China’s future.

At the end of the 80’s, a Chinese version of the statue of liberty was erected in Tiananmen Square. It came down on June 4th, 1989.

During the 90’s and in the years that followed, China was riding the wave of an economic transformation, while also increasing controls over the media, and the internet, and dissent. It was still possible to make a documentary film in 1991, but we arrived in China at a time when its citizens had been warned against unauthorized contacts with foreign reporters.

There was a delicate balance between what was possible, and what wasn’t. You had to find symbols, metaphors, indirect ways of getting beneath the surface of the official line. And at times, you simply had to take your chances — especially when told something you wanted to film didn’t exist, when you knew it did.

For example, signs of the Great Migration, the movement of rural Chinese to the cities seeking a better life. Already it was in the tens of thousands and would grow into the tens of millions. We found it in Chengdu, and we were able to film it.

We looked for ways in which young Chinese, especially, were seeking to find free expression:

In China’s first modern dance troupe, where a dancer told us: “I can express what’s in my heart, what I really want to say, I feel I’ve been liberated”…

In the lyrics of a song heard at a karaoke club: “I’m not the bad kid you say I am. My thinking has left you behind, this generation is mine, this is our time”…

At a nightclub owned, ironically, by the PLA: in the lyrics of a rock and roll band: “Perhaps we’ll sing until our world is turned around”…

And at the elite Middle School #4 in Beijing, whose graduates include the well-known dissident Fang Lizhi. When asked what they wanted to do when they graduated, there was this answer: “I think the job I do must be a little free, much freer from government control.”

And to a question about their interest in America: “I want to go to the United States to study, to see how life could be. You can’t find it anywhere else in the world, only in America. All of us want to go.”

Yenan, 1991, China After Tiananmen

There was, of course, much more to the story in 1991, in a China whose leadership still was shaken by the events of 1989. A vice-minister who agreed to be interviewed had this to say: “When we open the window of reform, some flies and mosquitoes may come in, and when they do, we’ll just kill the flies and mosquitoes.” Talk about metaphor.

In 2008, it became clear, that for foreign reporters anyway, things were not getting better. In that year, we asked permission to film at locations in Beijing for a documentary about an American who had joined the Chinese communist party and became a leader, and victim, of the cultural revolution.

The request went all the way to the State Council. The answer: send us a shot list. We let it go at that.

The pressure on reporters, foreigners and Chinese, would become more and more controlled and restrictive in the years that followed. At all times, of the many challenges facing the journalist in China, perhaps the biggest has been reporting by American standards and expectations in a country whose traditions and practices are very different from our own.

The American reporter in China was squeezed between two very different concepts of journalism’s role and purpose. If you followed all the rules, all the time, you might as well have been working for CCTV. Transparency and accountability could never be taken for granted. There has been plenty of room for not getting the story right, and for distrust on both sides. Chinese gate keepers don’t make it any easier. But you can’t stop trying.